Key points

- A significant proportion of household waste that goes to landfill is made up of food and organic waste. Food and organic waste is a particular problem in landfill because when it decomposes, it releases harmful greenhouse gases.

- Your household can take action to reduce food waste by improving your food shopping and storage habits and making the most of any leftovers. This saves money and reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

- You can also recycle food and other organic waste in your home. Compost bins, worm farms, and other new methods can all reduce the amount of waste going to landfill, and produce valuable compost and fertiliser for garden areas.

- New community initiatives connect people with organic waste to a variety of local recycling systems that can generate compost for use in the local community.

Understanding food and organic waste

Organic waste generated in the home mainly comprises food waste and garden organics. The amount generated varies widely, depending on several factors such as the type of home (a small flat with a balcony or detached house with a large garden), the number of people living in the home, and how residents deal with food and garden organic waste.

A third of all food produced globally ends up as waste. In Australia, an estimated 7.6 million tonnes of food intended for human consumption is wasted every year (Food Innovation Australia Limited, 2021). This preventable waste costs the Australian economy $36.6 billion each year. The amount of food wasted by households alone is over 2.4 million tonnes per year. On average, this costs each household approximately between $2,000 and $2,500 per year.

Producing less food waste will also prevents greenhouse gas emissions. These emissions occur during the production, transport and sale of food, and with most food waste ending up in landfill, it then also produces emissions as it decomposes.

Global policy aims to halve food waste by 2030. In Australia, the National Food Waste Strategy provides a framework to support collective action towards achieving this goal. Many state, territory and local governments are contributing to this by helping households reduce and recycle their food and organic waste to prevent it ending up in landfill.

Reducing and recycling food and organic waste

Reducing food waste

Some food waste is unavoidable, such as the bones from meat or peelings from fruit and vegetables. However, there is plenty of opportunity to reduce the amount of avoidable food waste ending up in landfill. Avoidable food waste includes leftovers created when cooking too much, or food that is edible, but spoils if left too long.

Tips for reducing avoidable food waste include:

- checking what you already have in your fridge, freezer and pantry before shopping

- planning your meals and shopping with a list so you only buy what you need

- buying in bulk only if you can store things correctly

- making sure you prepare and cook the right amount of food

- encouraging smaller servings

- storing leftovers correctly

- finding ways to reuse leftovers - OzHarvest has some great recipe ideas for leftovers.

Photo: Maeli Cooper

The Love Food Hate Waste Program, originally launched in the United Kingdom in 2007, focuses on reducing food waste and has been adapted for the Australian context in some states including New South Wales and Queensland. Anyone can access and use the advice, tools and videos developed to help householders reduce their food waste and save money:

- NSW Love Food Hate Waste 6-step Food Smart program

- Brisbane City Council Love Food Hate Waste program.

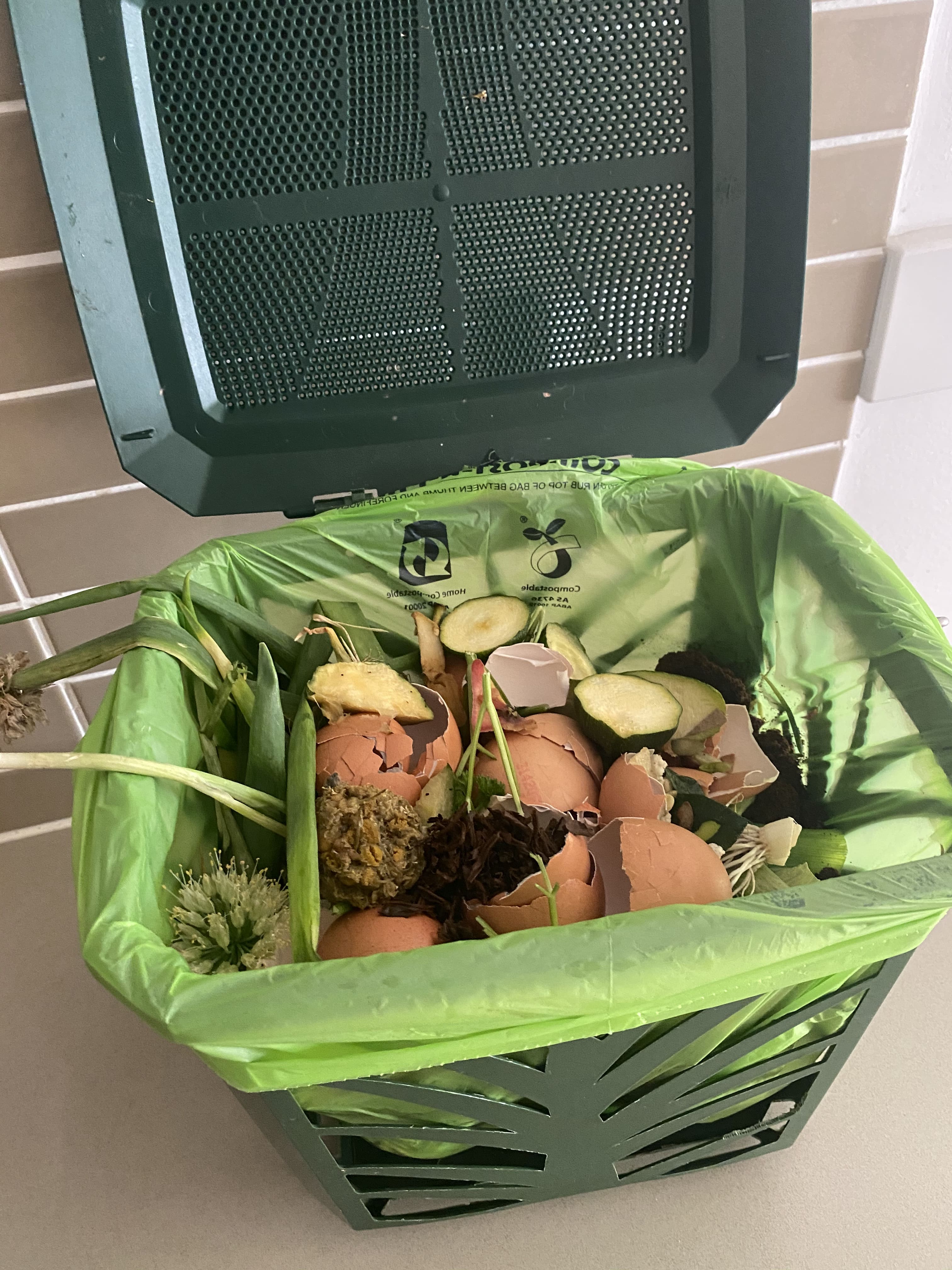

Recycling organic waste at home

When organic waste is unavoidable, there are several ways to treat and recycle it within the home. Many Australians have recycled their home organic waste for decades in simple compost bins, but there are now a range of treatment methods available, depending on the type of waste to be recycled.

The Compost Revolution program currently working with over 30 councils across Australia, helps householders to recycle their organic waste. The program provides online advice and tutorials as well as access to subsidised equipment, from kitchen caddies to worm farms.

Tip

Many local governments also provide advice and subsidies for equipment. You can check with your local government or at Compost Revolution.

Recycling methods

Treatment methods now come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, for large households with a garden through to single occupancy households with little or even no outdoor space. All treatment methods will require some level of maintenance to keep the system healthy and avoid pests and smells.

Common ways to treat organic waste in the home include:

-

Compost bins – These range from homemade bays made with recycled materials, to traditional plastic open-bottom bins or single- or dual-compartment tumblers. Costs similarly vary. Compost bins are suited to households with both garden organic waste and food scraps (excluding food waste such as meat, dairy and pasta) and where you can use the compost generated in gardens and pot plants.

The bins are best kept in a warm, semi-shaded spot in the garden with easy access to ensure ongoing use. To keep your compost bins healthy, you will need a mix of 50/50 green to brown materials, where green are the wetter materials like food waste and grass clippings, and brown are the drier materials like leaves or materials with a high carbon content such as old newspapers. The material in the bins needs regular turning to maintain oxygen levels and a little water to keep them moist but not too wet.

Compost bins can turn food and garden waste into valuable compost for your garden

Compost bins can turn food and garden waste into valuable compost for your gardenPhoto: Getty Images

-

Worm farms – These units are inexpensive and are typically layered boxes where the worms live, plus a bottom layer where worm wee collects. Worms need to be bought separately. The systems work best if you do not have garden waste to treat. They can be good for smaller households with limited food scraps, or homes with limited outdoor space such as flats or apartments. Food scraps such as meat, dairy, citrus or onions cannot be put into a worm farm.

Worm farms should be kept in a cool, moist, dark environment, out of direct sunlight and extreme temperatures. A reasonable temperature range is between 10 and 30°C. The liquid or worm wee collected at the bottom of the unit needs to be regularly drained through the tap and can be used as a liquid fertiliser at a ratio of 1:10. The vermicast produced, in the upper layers where the worms live, needs to be removed occasionally and can be used sparingly as a solid fertiliser for the garden or potplants.

Worm farms are good for smaller households

Worm farms are good for smaller householdsPhoto: Felicity Woodhams

-

Bokashi buckets – These systems normally have a capacity of 10 to 20L and can fit under the sink. The systems treat the food waste through a fermentation process, which is accelerated with the help of an additive containing microbes, which needs to be bought separately and applied regularly. The bins are inexpensive but the additive is an ongoing cost. This type of treatment best suits those that do not want or need to treat garden waste. They can be good for smaller households, homes with small gardens, and flats or apartments with no garden. They can treat a greater range of food scraps than worm farms, including meat, dairy, citrus, onions, bread, and small bones.

The food waste in the bucket reduces in volume as nutrient-rich liquid drains from the tap at the base. This concentrated liquid needs to be mixed with water at a ratio of around 1:100 before being added to plants as a liquid fertiliser. The semi-solid material in the bokashi bucket needs to be removed at regular intervals. It typically needs to be buried for further composting, but there are methods you can use to finish the composting process even if you live in a flat or apartment with no garden.

Photo: Wikimedia (Dillard421)

Less common treatment methods beginning to come on the market in Australia and suitable for the home now include:

- Home dehydrators – Typically having a capacity of 1kg, such units grind, sterilise and dehydrate virtually any food scraps including small bones, reducing the scraps by up to 90% in 3 hours. These are relatively expensive and will also use electricity to run – some of the 500W units are reported to use up to 1kW of electricity each cycle. The units often need filters to be replaced every 3 to 6 months. The resulting output material needs to be left for more than a week before being added to soil at a ratio of 1:1.

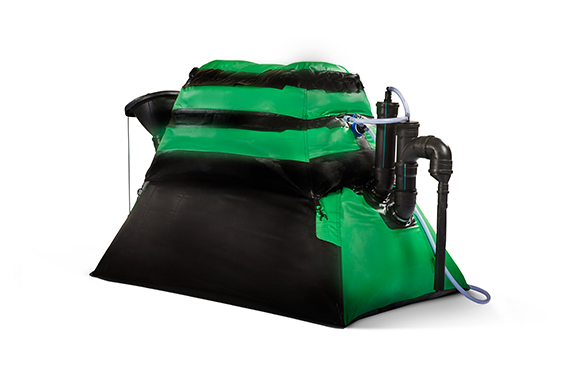

- Home anaerobic digestion – For homes with more space, food scraps can be used to produce biogas in a mini version of the industrial units used in many parts of the world. The units produce gas that can be used in specially converted stove tops. For an average family, with an average volume of food waste, these units typically produce enough gas for up to 2 hours of cooking time per day. A secondary by-product is a liquid fertiliser that can be diluted and put on the garden. These units are relatively expensive.

Photo: Wikimedia (BiogasME)

There are also more specialised treatment systems that can deal with other organic waste types such as those generated by pets like cats and dogs. It is generally recommended these materials should not be treated in the above systems due to the risk of pathogens in the end product.

Design considerations

Whether you are building a new home or undertaking home improvements, waste management systems are best considered at the design stage so they can be seamlessly integrated into house and landscape design. This helps to make household waste management easy. Consider:

- integrating multibin sorters into kitchen design, so that waste can be easily separated into different streams for recycling and composting

- designing and landscaping outdoor areas to accommodate adequately sized, functional storage areas for compost bins, worm farms and bins for recycling and waste

- ensuring there is easy access from kitchens to bin storage areas

- designing access paths so that bins can easily be wheeled to their collection point on the street, and allowing for wheelbarrow access to compost bins.

Photo: Caitlin McGee

Recycling organic waste in your community

New ways to support communities to treat organic waste are becoming more common.

In many areas, local governments have been trialling and running programs to help those in flats or apartments who have limited outdoor space to be able to recycle their food waste. For example, the City of Stonnington in Melbourne provides subsidised communal worm farms, free kitchen caddies and access to assistance and on-site training workshops to encourage residents in blocks of flats to set up communal food waste recycling facilities on-site.

Check with your local council to find out if they have any programs to help you set up communal food waste recycling systems in your building.

Online resources include:

- Sharewaste – Sharewaste is a mapping and communication app which was started in Sydney in 2016 and now has an international network with over 70,000 members. It enables individual households with food waste to connect with those with worm farms, composters, and chickens in their local area who can potentially receive organic materials for local treatment and use.

- Community gardens – The Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network can tell you if there are any community gardens near you and how to set one up if you want to collaborate with your neighbours on community-scale organics waste recycling.

Kerbside collection services

A range of residential organics kerbside services are provided by local governments. These vary depending on the local government area. As of March 2023, around 27% of local governments have introduced a food organics and garden organics (FOGO) kerbside collection service, 16% a garden organics only (GO) kerbside collection service, and some local governments also provide a food-only organic (FO) waste kerbside service.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water provides an interactive map that displays local government areas where FOGO, GO or FO kerbside collection services are provided. This map is regularly updated as additional services are rolled out.

The organic waste is typically transported to organic recycling (composting) facilities and processed into recycled organics products used in landscaping, urban amenity and civil projects, and in agriculture. Some organic material is taken to anaerobic digestion plans where it is converted into gas for electricity and heat generation for use in households.

Note

Your local council may provide equipment such as a kitchen caddy free of charge, to help and encourage you to collect and divert organic waste from landfill. Contact your local government if you are unsure about the services available, or to find out how to get an organics (green) bin.

Photo: Kempsey Shire Council, NSW EPA and NSW Environmental Trust

New technology

As our cities grow and more people shift to apartment living, so too will the way waste is being managed.

Currently used predominantly in the commercial sector and uncommon in the residential sector, large-scale dehydrators will likely be used within residential blocks to treat food waste from entire buildings on site. Dehydrators can reduce the volume of separated food waste by up to 90% before it is transported for additional treatment. Depending on the circumstances and system operation, the energy use of the dehydrator can be offset by the reduced waste transportation costs.

Similarly, anaerobic digestors are likely to be used in mixed-use precinct-scale developments for a combination of residential and commercial organics waste streams to produce on-site biogas that can be used to heat water or produce electricity. This technology has the added bonus of producing nutrient-rich digestate as a potential soil improver for garden areas.

Careful consideration will be needed to assess the viability of these new technologies in a residential block or mixed use precinct. Issues to consider include planning, space, logistics, regulations, and the volumes, quality, and contamination levels of input materials from each block.

Finally, similar to other countries, the waste industry will potentially move towards pay-as-you-throw waste management and radio-frequency identification weight-based billing for individual households. Such systems will provide more incentives for householders to reduce and, where this is not feasible, recycle their food and organic waste.

Photo: Getty Images

References and additional reading

- APC (2019). SSROC kerbside waste audit: regional report [PDF], APC, Sydney.

- Australian City Farms and Community Garden Network.

- Australian Government (2023). Food Organics and Garden Organics (FOGO) interactive map (arcgis.com)

- Australian Government (2017). National Food Waste Strategy: Halving Australia’s food waste by 2030. Australian Government, Canberra.

- Blue Environment Pty Ltd (2022). National waste report 2022, prepared for the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Australian Government, Canberra.

- Champions 12.3 (2017). SDG Target 12.3 on Food Loss and Waste: 2017

progress report. - Compost revolution.

- Fight Food Waste Ltd (2020). Stop Food Waste Australia.

- Food Innovation Australia Limited (2021), National Food Waste Strategy Feasibility Study Final Report.

- Ozharvest (2022). www.ozharvest.org/use-it-up

- NSW Environment Protection Authority (2017). NSW Local Government waste and resource recovery data report 2014–15. New South Wales Government, Sydney.

- NSW Government, Love Food Hate Waste 6 Step Food Smart Program,

- Sharewaste mapping app.

- Turner A, Fam DM, McLean L, Zaporoshenko M, Halliday D, Buman M, Lupis M and Kalkanas A (2018). Central Park precinct organics management feasibility study, OPUS 68.

Learn more

- Read Landscaping and garden design to discover how to make the most of your outdoor areas

- Explore Buying an apartment to find other considerations when you are in the market for an apartment

- Review Reducing water use for ideas on using less water both indoors and outdoors

Authors

Principal author: Andrea Turner, 2020

Updated: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, 2023